EXPLAINING OUR VIEWS ON TOO MUCH CAPACITY

TOO MUCH SEAT CAPACITY OR THE WRONG SEAT CAPACITY MIX? WHETHER ASMs OR DEPARTED SEATS ARE THE MEASURE, EACH POINTS TO A DOMESTIC INDUSTRY WITH TOO MUCH CAPACITY.

and 2019 IS NOT THE RIGHT BASELINE BENCHMARK

Swelbar-Zhong Consultancy

PREAMBLE

The first version of this paper was made available to the public on July 7, 2024. Like in the past, it focused on the relationship between the change in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and the change in Domestic Available Seat Miles (ASMs) between 2010 – 2023 within the eras of capacity deployment as defined in several academic and industry writings. In the past, ASMs were used as the measure of capacity.

On July 11, 2024, Delta Air Lines reported its 2q’2024 earnings to the analyst community. During that call, a question was asked about how Delta views the relationship between ASMs and GDP. Glen Hauenstein answered that he believes that seats, or departed seats, are a better measure than ASMs. “It’s really the seat count that is most important because we don’t sell ASMs, we sell seats”.

He goes on and “when you think about our capacity growth although it was 8%, we only grew our seats at about 5% or less. So, there is a stage length difference. And our stage length is a little bit longer than we had in the plan. So, I’d call it back to, let’s not talk about ASMs. Let’s talk about seats within the theater. So, I think that’s a much better representation of what the industry is facing and one we ought to all key in on as we move forward and try to figure out where the industry is going”.

As we were early in humbly producing thoughts attempting to measure overcapacity, this version will use the departed seats:GDP relationship as it adds value. Domestically, stage lengths are not that different between airlines so many of the calculations made in the previous work using ASMs are not dramatically different. It is hard to argue with the seats are better than ASMs in the domestic arena. Then again, we measure unit revenue and unit cost performance per ASM.

So, the narrative below is based on domestic departed seats. The conclusions are largely the same. The industry has too many domestic seats to support pricing needed given the trajectory of costs. And the two sectors that have aggressively put seats into the domestic space produce the kind of product that the air travel consumer will only pay so much for.

OVERVIEW

The current airline sector capacity makeup of the domestic airline marketplace in the U.S. posits many questions. But every question needs some input on the level of capacity to answer properly. But capacity is different from the old capacity just like a seat is no longer just a seat. If the level of today’s domestic departed seats flown by all sectors is deemed to be too much, then I surmise that the damage (adding too many domestic seats) began in 2015. There was little in the economy that justified the rate of growth in domestic commercial airline service during the period, particularly by Southwest and the ULCC sector.

It was June 6, 2017, when Doug Parker, then American Airlines’ CEO told shareholders at the annual meeting that: “My personal view is that you won’t see losses in the industry at all”. He went on: “We have gotten to the point where we like other businesses will have good years and bad years, but the bad years will not be cataclysmic. They will just be less good than the good years.”

The analysis suggests that 2019 is not the right baseline benchmark that we use to gauge the industry’s recovery either. The better benchmark period is located somewhere between 2017 and 2018. Then using a benchmark earlier than CY2019 as the basis for domestic capacity recovery would result in a number that many would say is too far ahead of itself today. Particularly if you buy the fact that too many domestic seats were deployed in CY2019. Sure, we have increasing numbers of passengers in the system. It is just that the capacity deployed is only generating sufficient revenue for 2-3 of the 13 large airlines operating.

Beginning in 2020, when assessing domestic industry capacity levels, it became time to think more about the respective airline sectors and the capacity produced by each rather than just looking at the industry total capacity without regard to airline or airline sector. This analysis points directly at the ULCC sector and Southwest as having too much domestic capacity deployed in CY2023. The irony is that each has a product that is less in vogue with the air travel consumer – which is single-aisle, single-class service only and amenities that are few when compared to the network and hybrid carriers. Passenger load factors and the revenue line underscore this on a sequential basis.

There have been too many instances when adding capacity results in less revenue. Never good.

Finally, stakeholders across the spectrum love to lionize 2019 as the baseline benchmark highlighting an economically and financially healthy industry. From a perspective of financially healthy airline capacity the better year would have come before 2019. Either baseline would say that too much capacity has returned too fast depending on the sector. For an airline that operates within the ULCC sector, smaller in 2023 is likely a better position as opportunities will become available for some but not all.

The one thing where Parker was right is that he made those comments in 2017 and not 2019.

INTRO – THE CAPACITY DISCIPLINE ERA (2010 – 2014)

Since the Pandemic-induced changes in the level of capacity deployed by the US airlines have altered the thinking of participants and stakeholders across the board, 2019 quickly became the baseline benchmark used to assess the state of the recovery. But is 2019 the right baseline benchmark?

It is complicated. This attempt to put numbers measuring whether the US airline industry’s capacity either over/under capacity measured by departed seats was triggered in the second half of 2023 when pricing fundamentals imploded – particularly for Southwest and the ULCCs. I will reference the eras of capacity deployment that Mike Wittman at MIT initially studied beginning with the Capacity Discipline Era that ran from 2010 – 2014. I have continued to add to that work.

The underlying assumptions made during the era were fundamental to any assessment of the industry’s economic and financial health. The foundational data point forever used has been the change in the Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Capacity Discipline became defined as the period where US domestic capacity or Available Seat Miles (ASMs) would grow at a rate slower than the rate of growth in GDP. We have assessed the ASM:GDP relationship – now based on comments from Delta we will focus on the Departed Seats:GDP relationship.

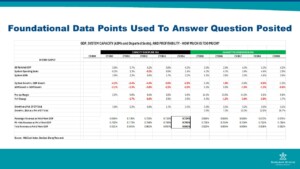

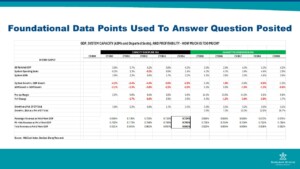

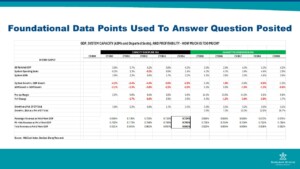

Between 2010 and 2014, the GDP grew at a simple year-over-year average rate of 4.0% while system departed seats grew at a simple average rate of .6% and domestic departed seats grew at a rate of -.2%. Domestic departed seat growth over the period was 4.2 points less than the growth in GDP and system departed seat growth averaged 3.4 points less than the growth in the economy.

Much was written about this period of capacity deployment. Wall Street fully embraced it (still does) causing Washington to become concerned about the fact that even Southwest would grow its capacity slower than the rate of growth in the economy in concert with the network carriers. It was an airport industry nightmare as any airline growth became a zero-sum game to add capacity.

The industry was emerging from the damning effects of the Great Recession. Southwest no longer had an oil hedge book resembling what they had in place between 2004 – 2008 that gave them an additional competitive cost advantage relative to virtually all other airlines. They too needed to find revenue to offset the loss of the significant advantages gained from hedging oil. Calendar year 2014 would be the only year in the era where Southwest would grow domestic departed seats faster than the change in GDP.

The hybrid carriers comprised of Alaska, Hawaiian, and jetBlue grew domestic seats in line with the average growth in the economy largely because jetBlue was still in its infancy and wanting to grow. All the while, the ULCCs comprised of Allegiant, Frontier, Spirit, and Sun Country would grow seat capacity at a rate 4.5 points faster than the growth in the economy over the 2010 – 2014 period. This is where averages often do not tell the whole story. In 2014, these ULCCs would increase seats capacity by 14.5% or 10.2 points faster than the growth in GDP. The real-life application of the Prisoner’s Dilemma begins here.

The relationship between the growth in capacity at rates less than the economy resulted in the industry pre-tax margin averaging 2.4%. The average of 2.4% includes the fact that the industry pre-tax margin in 2014 was 5.8%. In 2014, passenger revenue as a percent of nominal GDP was .724%; passenger and ancillary revenue as a percentage of GDP was .761%; and total revenue as a percent of GDP measured .961%. It could be surmised that the industry was set up for a long profitable period because of the discipline employed over the 2010 – 2014 period. Capacity restraint precedes improved profitability.

Finally domestic departed seats as a percentage of system departed seats averaged 79.0% – but was trending downward throughout as international flying was increased. At year-end 2014, Southwest domestic departed seats would comprise 20.3% of the industry total. When the ULCC carriers are added to Southwest, the share of (U)LCC narrowbody, single aisle domestic departed seats would comprise 25.1% of all domestic departed seats.

The ULCC sector did not play along with the concept of capacity discipline but by 2014 they did their own jailbreak seeking parochial riches by growing their seat offering at fast rates to win market share. And they did. For CY2010, the ULCCs were 18.5% of the size of Southwest. By 2014, they would be 23.5% of the size of Southwest when measured by domestic departed seats.

The landscape was changing.

THE CAPACITY REGENERATION ERA (2015 – 2019)

This era was dubbed the capacity regeneration era (2015 – 2019) as carriers began to grow at increasing rates relative to the economy driven by the ULCC sector winning share not only versus the Big 3 airlines of American, Delta, and United but Southwest too. Overall, domestic departed seats would grow less than one-half of a percentage point faster than GDP. During this era, domestic departed seats would average annual growth of 3.8% versus -.2% during the capacity discipline era.

However, the story would be found when assessing the growth within the respective airline sectors – network, Southwest, hybrid, and the ULCCs.

System (domestic + international) ASMs would grow an average of 3.7% over the period relative to the average growth in GDP of 4.1%. It was during this period that other network changes were taking place as well. System departed seats would grow faster than system ASMs reflecting the shorter stage length flying found in the domestic arena.

The Big 3 grew departed seats over this period by an average of 2.9% that equated to an average of 1.2 points less than the growth in GDP; this is a period that began to put Southwest under a different light as it would grow seat capacity greater than the rate of growth in GDP in 2015 and 2016, but would grow capacity at a rate 2.6 points slower than GDP between 2017 – 2019 and would actually reduce departed seats in 2019 versus 2018. Southwest’s pre-tax profit margin began to decline each year beginning in 2017.

The hybrid carriers would add departed seats at a simple average annual growth rate of 5.3% over the period which was an average of 1.2 points above the growth in the economy. Each of the network carriers and Southwest grew domestic departed seats slower than GDP each year between 2017 – 2019. They would be joined in this capacity deployment decision by the hybrid carriers as well. Again, profit margins were falling as seat capacity deployment accelerated relative to 2010 – 2014.

Over this 2015 – 2019 period, the ULCCs would increase domestic departed seats by a simple average year-over-year rate of 16.7% which was 12.7 points faster than the growth in GDP. As each of the network, Southwest, and hybrid carrier sectors began to slow departed seats in the domestic space beginning in 2017, the ULCC sector would counter by increasing their growth rates. The commodity industry mentality.

Between 2015 – 2017, the industry would earn double-digit pre-tax margins. They would fall to high single digits in 2018. The absolute growth in domestic departed seats between 2015 – 2019 was equal to 16.9% of size of the domestic system in 2019. The growth in system departed seats over the period would be 16.9% of domestic departed seats in 2019. Domestic departed seats as a percentage of system departed seats would decline to 77% in 2019. Passenger revenue, passenger and ancillary revenue, and total revenue as a percentage of GDP would decrease between 5-7%.

Whereas each the network carriers, Southwest, and the hybrid carriers would slow their growth in departed seats relative to the economy in each 2018 and 2019, the jailbreak ULCCs just kept on adding with little to no change in strategy or product.

During this period, ULCC domestic departed seats as a percentage of Southwest’s domestic capacity output would grow from 23.5% in 2014 to 42.6% in 2019. Between 2015 – 2019 the industry added 168 million domestic departed seats. That growth equates to an airline 16% less than the entirety of Southwest’s domestic seat footprint and nearly twice the size of the entire ULCC sector in 2019. The growth of 168 million domestic departed seats between 2015 – 2019 compares to domestic departed seats being less in 2014 than they were in 2010.

THE CAPACITY REGENERATION ERA REALLY WAS A SOUTHWEST CONUNDRUM

There are many operational and financial attributes that made Southwest THE vaunted competitor through 2014. Its capacity growth would be used to continually average down costs up and down the income statement; its capacity growth created a “juniority effect” that would translate into industry leading productivity of labor and non-labor assets; and its network was built on its reputation of being the low fare provider that would spur air travel consumers to drive to some alternative airport to take advantage of.

During this 2015 – 2019 period, the industry would add 168 million domestic departed seats. The network carriers would add 77 million, or 46.1% of the additions; the ULCC sector would add 46 million departed seats, or 27.5% of the Capacity Regeneration Era’s growth; the hybrid carriers would add 32 billion departed seats or 18% of the growth; and Southwest would add 24.7 million, or 14.7% of the growth. Not the same Southwest. And the critical ingredient of growth during this period was largely absent. In fact, the absolute level of departed seats flown by Southwest in 2019 would be less than in 2018.

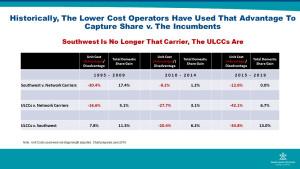

The chart above shows several critical competitive attributes. Until the recent application of the economic concept of cost convergence, lower cost operators would win the day particularly in the domestic and close in Latin markets. It was the cost advantage enjoyed by Southwest that fueled their rapid market share grab, particularly against the larger, pre-merger network carriers. Southwest used that cost advantage to the point where all the network airlines would file for protection under Chapter 11 of the US Bankruptcy Code. This would accelerate in the immediate post-9/11 period.

Whether cost convergence is a concept applied to lower costs or force lower costs higher, it is a competitive tool that should be accepted and not minimized in any way. Now in place, can the revenue environment support all capacity in place? If yes, can acceptable margins be earned?

Southwest’s ability to win the share of departed seats added by it and the network carriers would dissipate between 1995 – 2014. During the Capacity Discipline Era, and despite its cost advantage relative to the network carriers, they would only realize an incremental 1.2-point gain in of the capacity added by the two sectors. It would be the ULCC sector that would use its newfound cost advantage relative to Southwest to win a greater share of the capacity added.

But it would be the 2015 – 2019 period where the ULCC sector would use their cost advantage to grow and win share at the expense of the network carriers to a degree but would be a bigger winner of share when capacity was added relative to Southwest. Between 2017 and the most recent reporting in 1q’2024, Southwest’s pre-tax margin would decline from 15.4% in 2017 year-over-year as the airline added capacity. Its margin would also decline in 2019 v. 2018 despite cutting capacity.

Simply, Southwest has matured to a point where its growth cannot be sustained utilizing a point-to-point model only. It needs to incorporate connectivity to fill its large airplanes as the ULCC sector reduces the historic reach of the catchment areas by offering service from airports that used to drive to fly Southwest. As this model evolves, can its historic way to generate revenue from a point-to-point network relying on local traffic now generate a different revenue mix of local and connecting revenue? Building connectivity and generating the revenue needed to offset increasing costs are challenging the very fabric of a still technology-bereft Southwest.

As Mike Levine wrote in 1992:

1) Size confers advantages and disadvantages. Networks can be an effective way to combine flows and economize on marketing costs, but they come with vulnerabilities to labor, operational and political problems and

2) LCCs can be successful, but they face major challenges in growth. A large LCC tends to be more vulnerable to labor cost pressures and must also compromise its commitment to point-to-point service to grow past the limits that route density places on those airlines.

THINK SOUTHWEST – HOW PRESCIENT!!

IS 2019 THE RIGHT BASELINE BENCHMARK?

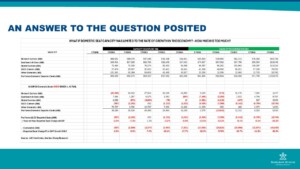

To answer the question posited, total system departed seats were increased at the rate of the economy’s growth between 2015 – 2019 for each airline sector. These pro forma departed seats were then subtracted from the actual departed seats flown. Based on this simple analysis (I did not lead or lag), or not so simple as it is an accepted approach across the industry, the ULCCs flew a cumulative total domestic between 2015 – 2019 of 34.4 million more departed seats than if the limit was the growth in the economy. Based on an average year-on-year percentage of departed seats flown over and above growth in the economy, then the 2019 seat capacity level is at least 10% too big versus what economic growth would suggest.

Going back to the positive results the industry achieved during the Capacity Discipline Era particularly when measuring all things revenue as a percent of GDP, departed seat growth was a -4.2% between 2010 – 2014 and only -.3% between 2015 – 2019. The relationship between slower capacity growth and an improved industry revenue performance when related to GDP is clear whether capacity is measured by ASMs or departed seats.

Ironic? I do not think so. The analysis thus far suggests that the 2019 baseline benchmark mindset is not the best one whether per sector or airline. The per-sector thinking should become part of any benchmarking that is performed. The question then becomes what is the best mix of departed seats inside of the domestic capacity portfolio that will produce sustainable results for all in the industry? Or is that possible given today’s portfolio mix?

THE PANDEMIC ERA – DURING AND POST (2020 – 2022, 2023 –

Any attempt to account for capacity deployed in either 2020 or 2021 seems like a rabbit hole that is not necessary to go down – therefore I am not. But this analysis is attempting to seriously answer two burning questions: 1) is 2019 the right baseline to benchmark against? and 2) given the financial condition of all airlines but Delta, United, and Alaska, domestic revenue generation suggests that there is too much capacity deployed today. Is the too much capacity by sector? If yes, HOW MUCH IS TOO MUCH?

The analysis of over/undercapacity begins with producing a calculation of how much capacity would be deployed by airline sector if the growth in GDP was the limiting factor. If that is the case, then there would have been 1.0 billion domestic departed seats flown in 2019 v. 997 million. On the surface, it suggests that the bottom-line domestic capacity produced was right where the economy would suggest it should be.

However, when assessing by sector, we know that all but the ULCCs were slowing any growth in seat capacity between 2017 and 2019 as margins were decreasing along with revenue production relative to GDP. The ULCCs however – the prisoners with the dilemma – were growing domestic seat capacity aggressively when compared to the other carriers. Assuming the ULCCs would have grown capacity no greater than at the rate of the economy between 2015 – 2019, then the sector would have flown a cumulative 34.4 million fewer departed seats. The 34.4 million number represents 40.1% of the size of the entire ULCC sector in CY2019. The analysis suggests that the ULCC sector would have at least 8% overcapacity at the end of 2023.

The analysis also suggests that Southwest was overcapacity at CY2023 by 7.4%. When the calculated overcapacity departed seats for Southwest and the ULCC sector are combined, there are 70 million too many departed seats flown by the two sectors in 2023. To put those 70 million departed seats in perspective, it is the equivalent of 30.9% of Southwest’s 2023 domestic departed seats and 70.5% of the ULCC sector’s 2023 domestic departed seats.

The analysis also points to 1.4% overcapacity in the network sector. Just like it will be important to analyze seat capacity by sector going forward, not only are up to 15% of the network carrier seats filled with passengers traveling to/from an international journey, based on their cabin configurations – economy seats comprise less than 70% of their seats flown. This has not been accounted for.

Whereas pre-tax profit margins show improvement between 2021 and 2023, the CY2023 profits were earned by 3 airlines, and this is likely to continue. The relationship between disciplined capacity deployment and airline profitability is undeniable. It is clear through this analysis that capacity – domestic seat capacity – needs to be removed. Latin American capacity in the Caribbean and Central American regions should carefully assessed as well.

Like any analysis done on the topic, it suffers a lack of any definitive takeaways during CY2020 and CY2021. Every ULCC and Southwest has announced, and/or continue to adjust, capacity reductions in 2024. Again, it cannot be overemphasized that the industry added 168 million domestic departed seats during the Capacity Regeneration Era. The ULCCs accounted for 46.2 million and Southwest 33 million in incremental domestic departed seats. Despite slowing growth relative to GDP over the last 3 years of the 2015 – 2019 period, margins were falling, revenue generation was falling short of expected growth, and domestic capacity was a greater percentage of system output.

FINAL THOUGHTS

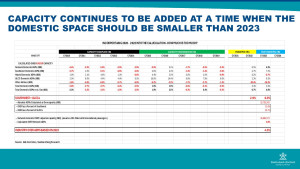

The two-year gap between 2019 and 2021 will not allow a definitive analysis of domestic departed seats that might need to be reduced today. However, the analysis points to a 2024 domestic industry that should be at least 5% smaller in absolute terms than in 2023 (GDP growth not known). However, it will be 3-4% larger despite the capacity cuts being made by airlines in all sectors and from the OEM dampening effects.

There is a role for the ULCCs going forward to be sure. Their timing to provide capacity to those with a thirst for travel during the Pandemic was near perfect. Southwest took advantage of the Pandemic opportunity as well to add nodes that would increase connectivity. Now the ULCCs and Southwest account for 33.4% of domestic departed seats. The cost structure that now permeates an industry that was formerly vigilant on low costs demands increasing revenue.

Neither Southwest nor the ULCC sector offer a product that can sustainably support 33% of the domestic seat capacity in the US. Using 2019 as the baseline benchmark is not the right data point as the industry was overcapacity then. Now we try to benchmark the industry’s capacity recovery as a percentage of a past point in time where it is now clear that the industry’s capacity growth was not supported by the growth in the economy – local, regional, or otherwise. And then it is compounded by overexuberant Southwest and ULCC growth during the Pandemic.

If the consumer proves to demand a premium airline product over the longer term, either the ULCC sector needs to get smaller, Southwest needs to shrink before it grows again, or both need to reduce their domestic seat footprint.

There is little in this analysis that tells me that the status quo is financially sustainable in its current form. The slides that follow track domestic capacity since deregulation. The analysis works backward from today’s airline makeup of the respective airline sectors. So, the Big 3 network carriers shown in 1978 would include all the carriers merged to form the respective groups today.

Whereas capacity deployed impacts a myriad of issues ranging from operational to financial, it just might be that it is the mix of airline capacity is becoming just as important, if not more important, than the sum of capacity produced by all sectors. Particularly in a mature market. This is not 1978, 1995, or 2002 Dorothy.

Recent Posts

2019 IS NOT THE RIGHT BASELINE BENCHMARK EITHER Note: 2q’2024 earnings calls begin this week; airline stocks were hit hard on July 5, 2024; blaming the OEMs (thinking they might be the savior for some) is not the only reason that airlines are cutting capacity and revising down revenue estimates; SkyWest’s market capitalization is 18% greater than the sum total of Allegiant, Frontier, Spirit, and Sun Country; remember when everyone believed that Frontier + Spirit = Juggernaut, the market cap of the combination is $1.4B; and how was the play Mrs. Lincoln? This has been a work in progress over

2019 IS NOT THE RIGHT BASELINE BENCHMARK EITHER Note: 2q'2024 earnings calls begin this week; airline stocks were hit hard on July 5, 2024; blaming

The iconic Rolling Stones song has many interpretations as to its meaning. All the way from worshiping the devil, to a role reversal in a male-female relationship, to suppression of individuality according to The Socratic Method. Over the last day or so I have been thinking about the number of happenings within the U.S. airline industry involving change agents and airlines. I was thinking about a role reversal and now it seems that change agents/banks have airlines under their thumb. Today, June 12, 2024, most applications of the bankruptcy code are not the same tools that they were in 2005.

The iconic Rolling Stones song has many interpretations as to its meaning. All the way from worshiping the devil, to a role reversal in a

Or has my airline been too slow to respond? Or … I am finally getting around to writing the first post on my new blog site. Writing anything before now has not been for a lack of want but rather to write I must feel it. And I have not been feeling it. But after weeks of – if someone does not win the game must be rigged, the one piece I always intended to lead with was Spirit CEO Ted Christie calling the U.S. airline industry a rigged game that only favors the Big 4 (American, Delta, United, and

Or has my airline been too slow to respond? Or … I am finally getting around to writing the first post on my new blog

#SmallerCommunityAirServiceDevelopment Yesterday's headline in the Lincoln Journal Star read: "Some sparks fly, but Lincoln Airport Authority board gives director a vote of confidence".